For years, the urge of owning a nice side by side shotgun in 20ga has floated around in my brain, briefly resurfacing from time to time, but never becoming overwhelming. Mostly because I didn’t hunt birds very often, and more importantly, because the price tag on most of these guns caused heartbeat irregularities and sudden surges in blood pressure every time I looked. Spending some time (days) in a hospital bed, waiting for a surgery spot to open, slightly delirious with hunger, I decided the time had come. And I knew which one I wanted: the CZ Bobwhite G2.

Contacting a local dealer, it quickly became clear that getting one ordered and imported from the US would come with very uncertain timelines. Months for sure, many months perhaps. But the dealer had an alternative. Apparently, the Turkish company Huglu makes the gun that CZ rebrands and sells as the Bobwhite model. And they had several Huglu shotguns in stock. Just not in the same finish, and not with the same barrel length, but cheaper and available immediately. So, a few days out of the hospital, we made the 5-hour road trip, one-way, to have a peek, and maybe bring one home.

First impressions

Honestly, I was not impressed by the looks of the gun, but my intention was to buy something that I would not be afraid to use. I wanted to drag this up mountains and ridges to look for blue grouse and ptarmigan, and put in the kayak when paddling for ducks, and drag through coulees and marshes, without having to worry about denting or scratching it. This one would probably fit that bill. The case colour hardening looked “thin”, and lacked the characteristics of a quality finish of that nature. It almost looked like a spray-on job, the colours vibrant, the pattern oddly regular. Hard to imagine this finish would last very long. The opening lever had a gold-coloured double-headed eagle, acceptable if stand alone, but rather boldly contrasting with the case colouring.

But the little gun fit! Eyes closed, shouldering, and finding the bead sitting right where it needs to be, was a pleasant surprise. Just shouldering the gun a couple of times had me sold, and forgiving it all the finish gaudiness. For a cost of just under a thousand Canadian dollars, it was not hard to justify this purchase. You wanted a gun over which you wouldn’t cry if you hurt it? Well, here it was.

After two years of use

The front trigger proved a bit heavy, and opening the gun requires a little downward tug on the barrels. The latter will likely improve with time, the former might require a polish, but in the field, it doesn’t seem to bother me. Hard to recall how many rounds went through this gun, or how many times I have taken it out into the field. Wild guesses would be 500-600 shells, and maybe thirty outings: hunting days, range visits and shooting during dog training and NAVHDA trial events.

The gun has not disappointed in terms of fit. If I do my job, don’t rush the shot, shoulder the gun cheek-first, keep my eyes on the birds, and don’t think, good things happen. I’ve made some amazing (in my world) shots, and had some events where I shot way above my pay grade. I attribute that mostly to the fact that my body and the guns dimensions just mesh. There are, however, a few things that need mentioning. It’s not all puppy dogs and rainbows.

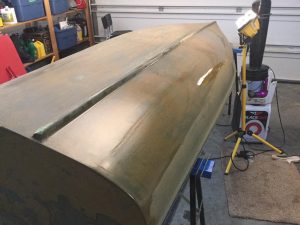

The finish. I knew it. It started coming off within months of using it. Around the grip and trigger guard it is completely gone, similar on the bottom corners of the action; any place where your hands regularly touch it.

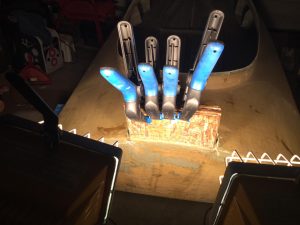

That was not the first issue. After shooting a few rounds of trap on the range, pins started coming loose. The pins that hold the cocking levers, and the one on the forend. As it happened at the end of the first season, I sent it back for a warranty repair. Months later the gun came back, with new pins installed, reportedly. The next range session, it happened again. Instead of sending it back once more, I used some epoxy to set them in place. So far so good. Time will tell.

That was not the first issue. After shooting a few rounds of trap on the range, pins started coming loose. The pins that hold the cocking levers, and the one on the forend. As it happened at the end of the first season, I sent it back for a warranty repair. Months later the gun came back, with new pins installed, reportedly. The next range session, it happened again. Instead of sending it back once more, I used some epoxy to set them in place. So far so good. Time will tell.

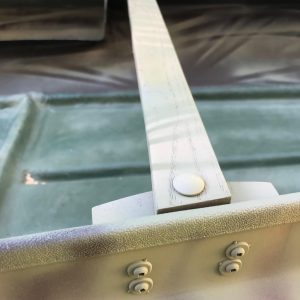

Unfortunately, there is more. The forend has started to wobble. There is side-to-side movement, where there should be none. Easily remedied for now, by putting some electricians tape inside the barrel channels, but in time this may need gunsmith intervention. For just two seasons of fairly light use, that is disappointing.

Unfortunately, there is more. The forend has started to wobble. There is side-to-side movement, where there should be none. Easily remedied for now, by putting some electricians tape inside the barrel channels, but in time this may need gunsmith intervention. For just two seasons of fairly light use, that is disappointing.

Conclusion

Since I am the worrying kind, I worry about what issue might arise next. Clearly, the quality of this firearm leaves something to be desired. Or should I be fairer, and say: you got what you paid for. The next step up in price would easily put five thousand devaluated Canadian dollars on the credit card, and likely one or two thousand more. Such a price difference would have to show itself somewhere, in this case a finish that doesn’t deserve the name, poorly fitting pins, and (perhaps) improperly hardened or lower quality steel on the forend lock.

Maybe it is time to start counting my pennies, regularly putting some change into an old tin, and investigate what options are out there on the right side of affordable, without getting cheap. In the meantime, I’ll keep taking this gun up and down ridges, through swamps and coulees, and hope that magic keeps happening, every time the operator doesn’t get too excited and messes things up. Unfortunately, that still happens way too often.

Frans